What is the evidence and research supporting SafeSide's approach to workforce education (InPlace Learning)? (in-depth)

For a video overview click here.

SafeSide Prevention offers a scalable and sustainable approach to educating the suicide prevention workforce called InPlace Learning. This evidence-based approach to workforce education leverages over 10 years of ongoing research. InPlace Learning provides teams with a map of best practices and evidence-based suicide prevention skills (the SafeSide Framework for Suicide Prevention) taught through an interactive workshop experience with ongoing support and connection to help teams effectively apply those skills in their daily work.

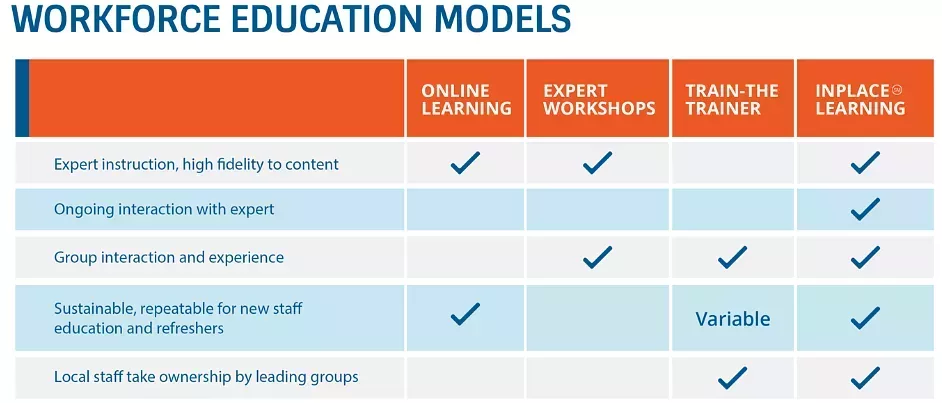

The components of InPlace Learning (see Figure 1) work together to support learners in adopting a common language and approach to suicide prevention and achieve deep learning outcomes that support practice change. This allows SafeSide to equip workforces with impactful suicide prevention education in a scalable way.

Components of InPlace Learning

Evidence Foundation of the InPlace® Learning

Expert-led workshops and large group trainings are costly and difficult to schedule in environments where time is at a premium. Train-the-trainer programs offer some increased flexibility, but rigorous research conducted by SafeSide founder, Dr Tony Pisani on a team led by Dr Madelyn Gould (Columbia University) and Dr Wendi Cross (University of Rochester) found that fidelity to content and quality of delivery suffers (Cross et al, 2014). Furthermore, the investment in train-the-trainer programs often does not return much training because of facilitator turnover or lack of practice (Cross et al, 2010). Individual online learning can increase knowledge (eg, Hoke et al, 2018) in an easily accessible format, but working alone in front of a screen can leave people feeling as if they are just ticking boxes rather than being involved in systemic change.

In response to a 2011 analysis of suicide prevention workshop education that called for a greater focus on patient outcomes (Pisani et al, 2011), Pisani and colleagues (2012) developed and tested a brief interactive curriculum that provided an authentic, skill-building experience for clinicians with a wide range of experience and responsibilities. A key goal was to unite personnel across service areas with a shared training experience and a common framework that could serve as a basis for ongoing educational activities. Beyond procedural knowledge and specific skills, the workshop provided a way of approaching and thinking through challenging situations via visual concept mapping, an educational technique based on constructivist learning theory (Mintzes et al, 1998; Novak, 1995) that had been tested elsewhere in health sciences education (Gonzalez et al, 2008; Srinivasan et al, 2008; Vacek, 2009; West, et all, 2000; Wilgis & McConnell, 2008; Willemsen et al, 2008), but not yet in suicide prevention training.

Participants in this novel 3-hour workshop gained knowledge and confidence (Pisani et al, 2012). They also gained skills in risk formulation as evidenced by improvements in objective-rated clinical documentation obtained immediately after the workshop. Staff in diverse clinical roles across acute, ambulatory and other services showed gains and benefits to a similar degree. Participants saw the workshop as highly transferable to the workplace, regardless of their service setting.

This workshop was adapted and tested for online delivery to primary care physicians and nurses (Pisani et al, 2021). Engagement in the online modules was high and learners showed large increases in knowledge and confidence. Although satisfaction with the training was high, this study also revealed opportunities for improvement that helped to inform the SafeSide InPlace Learning program. Specifically, this study revealed the need to incorporate the expertise of lived experience and a greater focus on video-based demonstrations to illustrate teaching points. The self-paced online format also left participants wishing for an opportunity to interact with one another and instructors on the practical and emotional challenges of supporting individuals with suicide concerns.

Conner and colleagues (2013) tested an important innovation: scenario-focused video training with group discussions designed to be delivered without the need for an expert facilitator. A coordinator convened small groups of substance use counsellors (n=273) across 18 states in the Veterans Health Administration services for the educational experience. The videos carried most of the burden of teaching and demonstrations with little preparation for the coordinator. The approach was well received, and the video-based group learning program showed improvements in participant knowledge, confidence, and suicide prevention practice behaviours.

Most importantly, this video-guided approach, hosted but not directed by a coordinator, provided a scalable way to provide team-based learning in suicide prevention – unlocking the potential for building ‘social capital’ through group interaction (Burgess et al, 2020), not just knowledge and skills. Incorporating social presence and collaboration in adult education are key ingredients for deep learning and the transfer of learning into practice (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004; Pai et al, 2014; Nielsen, 2009). Implementation science has consistently shown that the adoption of evidence-based practice and systems change occurs through networks and peer-to-peer interaction (Hammre et al, 2008; Shelton et al, 2019; Tenkasi et al, 2003). SafeSide added opportunities for staff to interact across organisations and regions through regular Q&A sessions with clinical and lived experience faculty based on findings that personnel who have contact with peers outside their own organisation are more likely to adopt new practices (Greenhalgh et al, 2004).

InPlace Learning emerged as a new, blended learning model for workforce education that includes:

The video guided InPlace Workshop comprised of 1) expert clinical and lived experience instructors, 2) skill demonstrations featuring real clinicians or staff and 3) regular opportunities for discussion and practice to support learning transfer.

Ongoing learning and engagement through monthly Q/A sessions with SafeSide faculty, an online Community of Practice connecting learners from organisations around the world, weekly email updates, brief video refreshers, and tools and assets to support the translation of skills into practice.

Regular updates to content based on emerging research, developments in the field and learner feedback.

Comparison of Workforce Education Modules

In a program evaluation of InPlace Learning, primary care providers and trainees perceived a greater ability to transfer training into practice from this video-based group experience (Centeno, 2020) as compared to the previous cohort with similar roles who experienced self-paced online modules only (Pisani et al, 2021). The InPlace Workshop also demonstrated strong educational efficacy and perceived relevance among a wide range of mental health and community workers in a large youth serving organisation (Donovan et al, 2023). Participants found the workshop transferable to their day-to-day work and reported improved knowledge and notable self-efficacy gains, especially for non-clinical staff who improved the most from lower baselines.

SafeSide Prevention continues to evaluate and evolve this best practice approach to workforce education by incorporating emerging research and ongoing program evaluation projects with international partners.

References:

Burgess A, van Diggele C, & Matar E. (2020). Interprofessional Team-based Learning: Building Social Capital. Journal of Medical Education and Curriculum Development, 7(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520941820

Centeno Valles, P. J. (2020). Program evaluation of a suicide prevention training for primary care. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Puerto Rico. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2487433558?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Dissertations%20&%20Theses

Conner, K. R., Wood, J., Pisani, A. R., & Kemp, J. (2013). Evaluation of a suicide prevention training curriculum for substance abuse treatment providers based on Treatment Improvement Protocol Number 50. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(1), 13-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.008

Cross, W., Cerulli, C., Richards, H., He, H., & Herrmann, J. (2010). Predicting dissemination of a disaster mental health “train-the-trainer” program. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 4(4), 339-343. https://doi.org/10.1001/dmp.2010.6

Cross, W. F., Pisani, A. R., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Xia, Y., Tu, X., McMahon, M., Munfakh, J. L., & Gould, M. S. (2014). Measuring trainer fidelity in the transfer of suicide prevention training. Crisis, 35(3), 202-212. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000253

Cross, W. F., West, J. C., Pisani, A. R., Crean, H. F., Nielsen, J. L., Kay, A. H., & Caine, E. D. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of suicide prevention training for primary care providers: A study protocol. BMC Medical Education, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1482-5

Donovan, S., Maggiulli, L., Aiello, J., Centeno, P., John, S., & Pisani, A. (2023). Evaluation of sustainable, blended learning workforce education for suicide prevention in youth services. Children and Youth Services Review, 148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.106852.

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 7(2), 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

Gonzalez HL, Palencia AP, Umana LA, Galindo L, Villafrade MLA. Mediated learning experience and concept maps: a pedagogical tool for achieving meaningful learning in medical physiology students. Advances in Physiology Education. 2008; 32:312–316. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00021.2007

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., & Kyriakidou, O. (2004). Diffusion of Innovations in Service Organizations: Systematic Review and Recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581-629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

Hammre, L and Vidgen, Richard, "Using Social Networks and Communities of Practice to Support Information Systems Implementation" (2008). ECIS 2008 Proceedings. 37. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2008/37

Hoke, A. M., Francis, E. B., Hivner, E. A., Simpson, A., Hogentogler, R. E., & Kraschnewski, J. L. (2018). Investigating the effectiveness of webinars in the adoption of proven school wellness strategies. Health Education Journal, 77(2), 249-257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896917734017

Mintzes, J. J., Wandersee, J.H, & Novak, J. D. (Eds, 1998). Research in Science Teaching and Learning: A Human Constructivist View. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Nielsen, K. (2009). A collaborative perspective on learning transfer. Journal of Workplace Learning, 21(1), 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620910924916

Novak, JD. Concept mapping: A strategy for organizing knowledge. In: Glynn, SM.; Duit, R., editors. Learning science in the schools: Research reforming practice. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1995. p. 229-245

Pai, H., Sears, D.A. & Maeda, Y. (2015). Effects of small-group learning on transfer: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 27, 79-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9260-8

Pisani, A. R., Cross, W. F., & Gould, M. S. (2011). The assessment and management of suicide risk: State of workshop education. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(3), 255-276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00026.x

Pisani, A. R., Cross, W., Watts, A., & Conner, K. (2012). Evaluation of the Commitment to Living (CTL) Curriculum: A 3-hour training for mental health professionals to address suicide risk. Crisis, 33(1), 30-38. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000099

Pisani, A. R., Cross, W., West, J., Crean, H., & Caine, E. (2021). Brief video based suicide prevention training for primary care. Family Medicine, 53(2):104-110. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2021.367209

Shelton, R.C., Lee, M., Brotzman, L. E., Crookes, D. M., Jandorf, L., Edwin, D., Gage-Bouchard, E. A (2019). Use of social network analysis in the development, dissemination, implementation, and sustainability of health behavior interventions for adults: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 220, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.013.

Srinivasan M, McElvany M, Shay JM, Shavelson RJ, West DC. Measuring knowledge structure: Reliability of concept mapping assessment in medical education. Academic Medicine. 2008; 83:1196–1203. https://doi/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818c6e84

Tenkasi, R. V., & Chesmore, M. C. (2003). Social Networks and Planned Organizational Change: The Impact of Strong Network Ties on Effective Change Implementation and Use. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 39(3), 281-300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886303258338

Vacek JE. Using a conceptual approach with a concept map of psychosis as an exemplar to promote critical thinking. The Journal of Nursing Education. 2009; 48:49–53. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090101-12

West DC, Pomeroy JR, Park JK, Gerstenberger EA, Sandoval J. Critical thinking in graduate medical education: A role for concept mapping assessment? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000; 284:1105–1110. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.9.1105

Wilgis M, McConnell J. Concept mapping: An educational strategy to improve graduate nurses' critical thinking skills during a hospital orientation program. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2008; 39:119–126. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20080301-12

Willemsen AM, Jansen GA, Komen JC, van Hooff S, Waterham HR, Brites PM, van Kampen AH. Organization and integration of biomedical knowledge with concept maps for key peroxisomal pathways. Bioinformatics. 2008; 24(16), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn274